All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit Know ALL.

The all Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the all Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The all and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The ALL Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Amgen, Autolus, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer and supported through an educational grant from the Hippocrate Conference Institute, an association of the Servier Group. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View ALL content recommended for you

Impact of caloric restriction and exercise on chemotherapy efficacy in young adult patients with B-ALL: the IDEAL trial

Being overweight or obese (OW/OB) has been associated with an increased risk of developing several different malignancies. More specifically, preexisting obesity has been associated with an increased risk of childhood B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL). Notably, as many as 40% of adolescents and young adult patients begin B-ALL induction therapy as OW/OB. Patients in this setting are known to have increased chemoresistance and measurable residual disease (MRD) positivity, which can lead to significant clinical ramifications and poor prognosis.

Recently, new scientific research has suggested that the negative effects of OW/OB physiology could be corrected with appropriate interventions. Therefore, Etan Orgel and colleagues hypothesized that inducing a caloric and nutrient restriction through diet and exercise could reduce gains in fat mass (FM), reverse overweight physiology, and improve chemosensitivity by decreasing postinduction MRD. The authors further hypothesized that lean patients could also benefit from this intervention.1

Study design

- The IDEAL trial was a proof-of-principle, non-randomized controlled trial in patients aged 10–21 years old, with newly diagnosed de novo, high-risk B-ALL (n = 40), who were beginning therapy with a Children’s Oncology Group-style 4-drug induction regimen; in comparison with a recent historical control (n = 80).

- Patients were categorized as OW/OB (body mass index [BMI] ≥85%) vs lean (BMI 10% to 84.9%). For patients ≥20 years of age, categories were defined using adult criteria (BMI ≥25 and BMI 18.5–24.9, respectively).

- The intervention (Table 1) was designed to induce a caloric deficit of ≥20% and commenced as soon as possible after chemotherapy initiation and before induction Day 4.

- The primary endpoint was percentage change in FM during induction.

- Secondary endpoints included end of induction (EOI) MRD and adherence/feasibility of the intervention.

- Body composition was measured at diagnosis and at EOI using whole-body, dual-energy x‑ray absorptiometry (DXA).

- MRD in the marrow was measured by flow cytometry. MRD-positive was defined using a threshold of ≥0.010% and detectable MRD as ≥0.000%.

- Feasibility was defined as completing ≥80% of weekly study visits for patients receiving induction chemotherapy.

- Adherence was defined as ≥75% to the prescribed intervention as assessed by the dietitian and self-reported for exercise.

- Integrated biology assessed biomarkers of theorized mechanisms for obesity-induced B-ALL chemoresistance. Plasma was collected at diagnosis and at the EOI to measure growth factors, cytokine concentration, and adipokines.

Results

Table 1. Summary of IDEAL intervention*

|

*Adapted from Orgel, et al.1 |

|

|

Education topic |

Approach |

|---|---|

|

Diet and exercise benefits during induction |

Integrated into physician conference and assessment of diet by a dietician and activity by a physiotherapist |

|

Food selection and portion control |

Individualized menus, Traffic Light, My Plate |

|

Safe exercise during chemotherapy |

Instruction, demonstration by physiotherapist |

|

Diet intervention |

Daily intake goal |

|

Caloric deficit |

≥10% |

|

Protein |

≥20% of total calories |

|

Fat |

<25% of total calories |

|

Carbohydrate |

<55% of total calories |

|

Low glycemic load |

<100/2,000 kcal |

|

Progression |

Caloric goal ±5% weekly |

|

Exercise intervention |

Goal |

|

Caloric expenditure |

≥10% |

|

Frequency |

Daily |

|

Intensity |

Moderate exertion |

|

Time |

15- to 30-min sessions (200 min/week) |

|

Type |

Aerobic exercise and resistance training |

|

Location |

Home-based |

|

Progression |

As tolerated |

- Out of the 40 patients enrolled, 36 were evaluable by DXA for the primary endpoint, 38 for MRD, and 39 for adherence and feasibility.

- Out of the 80 patients in the historical control group, 36 were enrolled in the body-composition trial with paired DXA results pre/postinduction.

- Selected patient characteristics and prognostic indicators are presented in Table 2.

- The IDEAL group had more adverse biological features vs the historical control; and

a higher BMI and FM at baseline.

Table 2. Patient characteristics*

|

SD, standard deviation. |

|||

|

Characteristic |

IDEAL trial |

Historical control |

p value† |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age, years |

|

|

|

|

Mean ± SD |

15.0 ± 3.0 |

14.7 ± 2.5 |

0.72 |

|

10.0–14.9, n (%) |

19 (48) |

46 (58) |

0.34 |

|

≥15, n (%) |

21 (52) |

34 (42) |

|

|

Sex, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

Female |

16 (40) |

37 (46) |

0.56 |

|

Male |

24 (60) |

43 (54) |

|

|

Ethnicity, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

Not Hispanic |

8 (20) |

14 (18) |

0.002 |

|

Hispanic, |

26 (65) |

66 (83) |

|

|

Not reported |

6 (15) |

0 (0) |

|

|

White blood cell count, ×103/μL |

|

|

|

|

Mean ± SD |

56 ± 117 |

50 ± 93 |

0.54 |

|

<50, n (%) |

31 (70) |

57 (71) |

0.52 |

|

≥50, n (%) |

9 (23) |

23 (29) |

|

|

Cytogenetics‡, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

Neutral |

18 (45) |

61 (76) |

<0.001 |

|

Favorable |

3 (7) |

10 (13) |

|

|

Adverse |

19 (48) |

8 (10) |

|

|

Unknown |

0 (0) |

1 (1) |

|

|

BMI category, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

Lean |

14 (35) |

45 (56) |

0.09 |

|

Overweight |

6 (15) |

9 (11) |

|

|

Obese |

20 (50) |

26 (33) |

|

|

BMI percentile, % |

79.5 ± 27.3 |

67.2 ± 32.8 |

0.03 |

|

Body composition§ |

|

|

|

|

Fat mass, kg |

25.2 ± 14.1 |

18.4 ± 11.3 |

0.04 |

|

% fat |

32.7 ± 9.6 |

27.8 ± 9.0 |

0.02 |

|

Lean mass, kg |

45.3 ± 14.7 |

39.5 ± 12.5 |

0.11 |

|

% lean |

64.4 ± 9.2 |

68.9 ± 8.5 |

0.02 |

Efficacy

- There was no significant difference in change in FM from preinduction baseline in patients receiving the IDEAL intervention versus the historical DXA control (median change, +5.1% vs +10.7%, respectively; p = 0.13).

- Patients who were adherent to the diet intervention, gained the least FM (median change, +2.4%).

- An exploratory subgroup analysis stratified by BMI at diagnosis showed that IDEAL patients who were OW/OB gained significantly less FM than OW/OB controls (median change, +1.5% vs +9.7%, respectively; p = 0.02) (Figure 1).

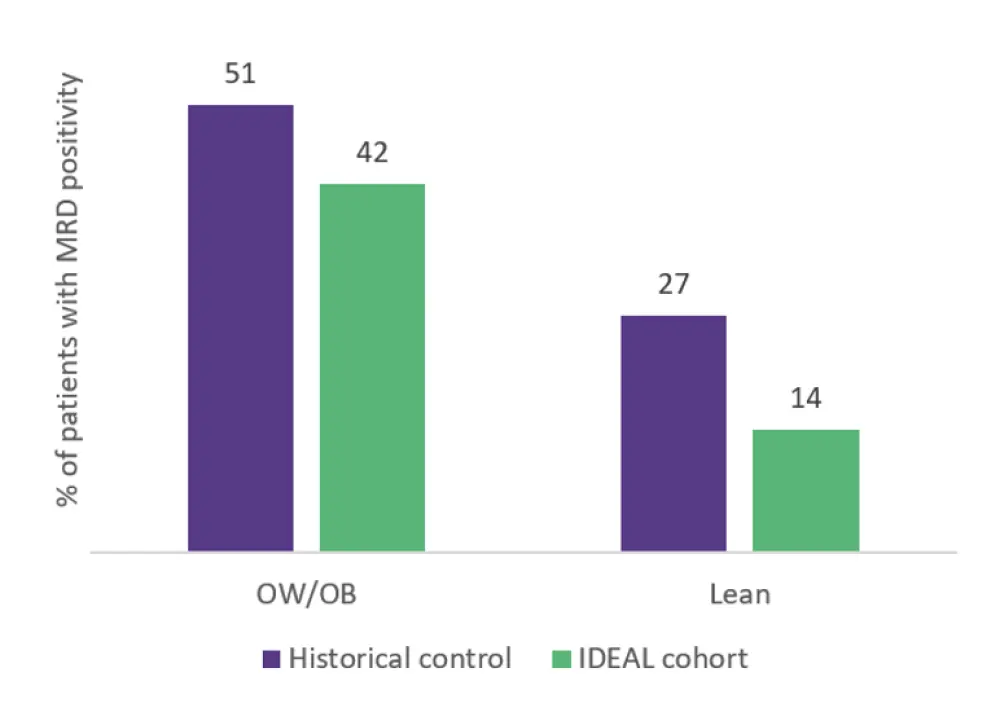

- Multivariable analysis demonstrated that the IDEAL intervention significantly reduced the risk of EOI MRD positivity compared with historical controls after accounting for prognostic factors (odds ratio, 0.30; 95% confidence interval, 0.09–0.92; p = 0.02).

- The IDEAL trial exceeded its adherence (≥75% of overall diet) and feasibility (86.5% completed study visits) thresholds.

- Cytokine concentrations analyzed at diagnosis found that leptin was positively corelated with FM (p < 0.001) and adiponectin was inversely correlated (p = 0.03), with the adiponectin-to-leptin (A/L) ratio (a marker of insulin sensitivity) inversely associated with FM (p < 0.001).

- After induction, there were no significant changes in leptin, but adiponectin and the A/L ratio were higher in the IDEAL cohort than the control, which indicated greater insulin sensitivity and less adipocyte dysfunction in the IDEAL cohort.

- In MRD-negative patients, A/L ratios were higher at EOI in the IDEAL cohort compared with the control cohort (p = 0.09) but not in MRD-negative patients (p = 0.45).

- Lean patients in the historical DXA control required significantly increased insulin for management of hyperglycemia compared with lean patients in the IDEAL arm of the study (32% vs 0%; p = 0.02). For patients who were OW/OB, there was no difference in insulin requirements between the IDEAL and control groups.

- Study participants not receiving exogenous insulin had significantly lower insulin levels at EOI in the IDEAL cohort versus the historical control (p = 0.02).

Figure 1. Prevalence of EOI MRD positivity stratified by BMI category1

BMI, body mass index; EOI, end of induction; MRD, measurable residual disease; OW/OB, overweight/obese.

*Adapted from Orgel, et al.1

Conclusion

This is the first prospective trial in a hematologic malignancy to demonstrate the feasibility and potential benefit of caloric restriction via diet and exercise on chemotherapy efficacy and disease response. The IDEAL intervention did not significantly reduce fat gain in the overall cohort compared with the historical control, however stratified analysis demonstrated benefit in patients who were OW and OB. After accounting for prognostic factors, the IDEAL intervention reduced the risk of EOI MRD in all patients. The insulin-glucose pathway and adiponectin were identified as potential mediators of chemoresistance and IDEAL efficacy. Limitations include poor adherence to the exercise component of the intervention, as well as the incorporation of a nonrandomized historical control.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content