All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit Know ALL.

The all Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the all Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The all and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The ALL Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Amgen, Autolus, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer and supported through an educational grant from the Hippocrate Conference Institute, an association of the Servier Group. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View ALL content recommended for you

Racial and ethnic disparities in survival outcomes among childhood and young adult patients with ALL

Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities across healthcare are a major concern. Previous analyses of treatment outcomes in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), undertaken 20–40 years ago, have reported inferior overall survival (OS) rates among Black and Hispanic children compared with other racial and ethnic groups; similarly observed among children from low socioeconomic backgrounds.1

Although optimized chemotherapy regimens and risk-stratified approaches based on minimal residual disease (MRD)/disease prognosticators have significantly improved OS and event-free survival (EFS) rates for children and young adults with ALL, little is known of the persistence of racial and ethnic disparities in these patients. Moreover, prior studies have attributed these disparities as secondary to differences in disease biology or insurance status, though the extent of their role in this context is not fully established.

The ALL Hub has previously reported on key approaches to addressing global socioeconomic disparities. Here, we summarize a recently published article by Gupta et al.1 in The Lancet Hematology, examining racial and ethnic disparities in survival outcomes for children and young adults across eight Childrens Oncology Group (COG) cohort trials; the impact of biological disease prognosticators and insurance status is also discussed.

Study design

This secondary analysis included children (aged 0–14 years) and adolescents and young adults (aged 15–30 years) with newly diagnosed ALL enrolled and treated in eight completed COG clinical trials (AALL0331, NCT00103285; AALL0232, NCT00075725; AALL0434, NCT00408005; AALL0932, NCT01190930; AALL1131, NCT02883049; AALL1231, NCT02112916; AALL15P1, NCT02828358; and AALL0631, NCT00557193) across the USA, Canada, and New Zealand between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2019. Race and ethnicity were combined and categorized as non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic Asian. The other categories comprised Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian, Alaska Native, or multiple races.

The primary endpoints were EFS, defined as time in years from study enrolment to first event including induction death; non-complete response (CR); relapse; death in response or developed secondary malignancy; and OS, defined as the time from study enrolment to death from any cause.

Secondary endpoints included relapse (overall, isolated bone marrow, CNS, or testicular), induction death in CR, secondary malignant neoplasm; and end-induction MRD.

Results

Of 24,979 eligible patients enrolled, 21,152 (84.6%) were included in the final study cohort analysis. Non-Hispanic White patients represented the largest cohort, followed by Hispanic patients, non-Hispanic Black patients, non-Hispanic Asian patients, and non-Hispanic other patients; cohort characteristics by racial and ethnic group are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient characteristics by racial and ethnic group*

|

B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; BM, bone marrow; CNS, central nervous system; MRD, minimal residual disease; T-ALL, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; WBC, white blood cell. |

||||||

|

Characteristic, % |

Total |

Non-Hispanic |

Hispanic |

Non- |

Non- |

Non- |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0–14 |

88.9 |

89.4 |

87.2 |

88.1 |

90 |

88.8 |

|

15–30 |

11.1 |

10.6 |

12.8 |

11.9 |

9.9 |

11.2 |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male |

56 |

55.5 |

56.6 |

58.6 |

56.6 |

57.7 |

|

Female |

44 |

44.5 |

43.4 |

41.4 |

43.4 |

42.3 |

|

WBC at presentation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

>50 |

80.7 |

81.4 |

79 |

77.6 |

81.3 |

82.5 |

|

≥50 |

19.3 |

18.6 |

21 |

22.3 |

18.6 |

17.5 |

|

Lineage in ALL |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

B-cell |

85.2 |

85.9 |

86.3 |

78.0 |

84.5 |

81.1 |

|

T-cell |

8.9 |

8.9 |

6.1 |

16.7 |

10.0 |

8.9 |

|

CNS status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CNS1 |

86.1 |

87.1 |

84.1 |

83.5 |

86.0 |

83.7 |

|

CNS2 |

11.6 |

10.7 |

13.4 |

13.1 |

11.7 |

15.1 |

|

CNS3 |

2.0 |

1.8 |

2.2 |

3.0 |

2.1 |

1.2 |

|

Cytogenetics† |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Favourable |

41.4 |

43.2 |

37.3 |

35.4 |

43.9 |

44.4 |

|

Neutral |

50.0 |

48.4 |

53.3 |

55.6 |

49.4 |

45.9 |

|

Unfavourable |

8.7 |

8.4 |

9.4 |

9.0 |

6.7 |

9.8 |

|

End-induction BM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<0.01 |

71.4 |

72.2 |

68.8 |

70.4 |

74.8 |

66.3 |

|

0.01 to |

9.8 |

10.0 |

9.6 |

8.7 |

9.5 |

10.7 |

|

0.10 to |

7.1 |

6.9 |

8.1 |

6.7 |

4.8 |

11.5 |

|

≥1.00 |

5.7 |

5.2 |

7.0 |

7.4 |

5.2 |

5.9 |

|

Insurance status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

US private |

61.7 |

67.7 |

48.7 |

48.5 |

61.2 |

42.6 |

|

US Medicaid |

27.1 |

18.6 |

50.0 |

48.8 |

14.0 |

23.4 |

|

International |

11.2 |

13.7 |

1.3 |

2.7 |

24.8 |

34.0 |

EFS and OS outcomes across racial and ethnic groups and insurance status

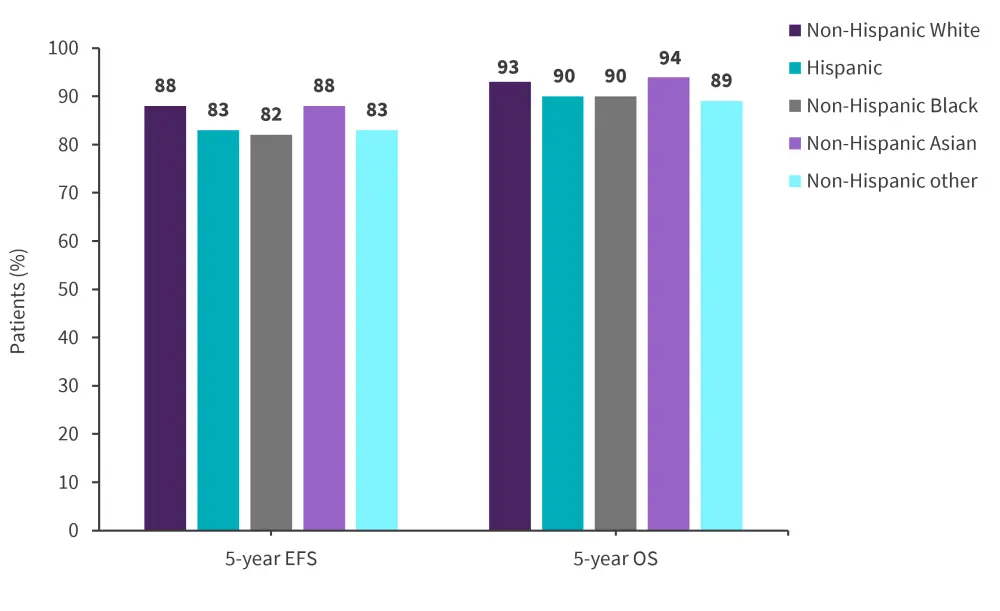

At data cutoff (June 30, 2021), the EFS and OS outcomes differed across racial and ethnic groups in the overall cohort, with higher survival rates observed among the non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Asian cohorts compared with the other three groups; the 5-year PFS and OS rates are reported in Figure 1. By lineage, survival rates were lower in patients with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) compared with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), and significantly different between racial and ethnic groups within B-ALL but not T-ALL cohorts.

Figure 1. 5-year EFS and OS across racial and ethnic groups*

EFS, event-free survival; OS, overall survival.

*Adapted from Gupta, et al.1

Across insurance status, 5-year EFS rates were highest among patients with international insurance (89%) compared with those who had U.S. private insurance (86.3%) and U.S. Medicaid (83.1%). The same pattern was seen in 5-year OS outcomes. By lineage, these disparities were only observed among patients with B-ALL, as similarly observed in survival outcomes by racial and ethnic group.

Multivariable analysis of EFS and OS outcomes by race, disease prognosticators, and insurance status

Inferior EFS outcomes among Hispanic patients within the full cohort were partially attenuated when adjusting individually for disease prognosticators or insurance status, and substantially attenuated when adjusting for both (hazard ratio [HR] decreased from 1.37 to 1.11). On the other hand, the increased risk among non-Hispanic Black patients was minimally attenuated when adjusting for both factors (HR decreased from 1.45 to 1.32). Further to this, across racial and ethnic groups with inferior outcomes in the full cohort, disparities in OS were greater than observed for EFS; this can be demonstrated by the difference in adjusted HR for EFS versus OS (1.33 versus 1.77) among the non-Hispanic other cohort. These patterns were only seen in patients with B-ALL.

Secondary outcomes across racial and ethnic groups

In the B-ALL cohort, there was a higher cumulative incidence of relapse, isolated bone marrow relapse, testicular relapse, death in remission, and earlier relapse reported among the Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic other cohorts compared with non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Asian cohorts. There were no significant differences in the risk of induction failure and risk of secondary malignancies across racial and ethnic groups (Table 2).

Moreover, the median time to relapse was shorter for patients with T-ALL versus B-ALL, although no significant differences were observed in secondary outcomes across racial and ethnic groups.

End-induction MRD positivity was more prevalent in non-Hispanic other patients vs non-Hispanic White patients (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 1.4–1.8; p = 0.031), Hispanic children were at no increased risk (1.1, 1.0–1.2; p = 0·23), and non-Hispanic Black children were less likely to be MRD positive (0.8, 0.7–1.0; p = 0·011). Among patients with T-ALL, only non-Hispanic Black children were more likely to be end-induction MRD-positive (1.5, 1.1–2.0; p = 0.0090).

Table 2. 5-year cumulative incidence of relapse and causes of treatment failure in B-ALL and T-ALL cohorts*

|

B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; BM, bone marrow; CNS, central nervous system; T-ALL, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. |

|||||||

|

Cumulative incidence, % (unless otherwise specified) |

Overall |

Non- |

Hispanic |

Non- |

Non- |

Non- |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

B-ALL cohort |

|||||||

|

Relapse |

9.5 |

8.6 |

11.2 |

14.3 |

7.6 |

10.8 |

<0.0001 |

|

Isolated BM |

5.5 |

5 |

6.5 |

8.5 |

4.6 |

6.5 |

<0.0001 |

|

CNS relapse |

2.9 |

2.6 |

3.5 |

3.9 |

1.6 |

3.6 |

0.0021 |

|

Testicular |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0 |

0.047 |

|

Median time |

1022 |

1099 |

930 |

812.5 |

1106.5 |

882 |

<0.0001 |

|

Induction death |

0.8 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

1.5 |

0.37 |

|

Death in remission |

1.9 |

1.6 |

2.8 |

2.0 |

1.8 |

3.7 |

<0.0001 |

|

Second malignant neoplasm |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

1.0 |

0.4 |

0.41 |

|

T-ALL cohort |

|||||||

|

Relapse |

9.3 |

9.9 |

7.5 |

9.3 |

6.8 |

6.7 |

0.66 |

|

Isolated BM |

3.3 |

3.3 |

2.8 |

3.7 |

4.9 |

0 |

0.54 |

|

CNS relapse |

4.5 |

5.0 |

3.9 |

4.0 |

1.9 |

3.3 |

0.55 |

|

Testicular |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.97 |

|

Median time |

425 |

443.5 |

514 |

333.5 |

344.5 |

793 |

0.22 |

|

Induction death |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0 |

0.9 |

3.3 |

0.31 |

|

Death in remission |

3.4 |

2.9 |

4.3 |

5.7 |

2.9 |

0 |

0.19 |

|

Second malignant neoplasm |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.7 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

0 |

0.18 |

Conclusion

This analysis demonstrated persistent and substantial disparities in outcome across racial and ethnic groups for patients with B-ALL; however, this was not seen in patients with T-ALL. Multivariable analyses established that these disparities cannot be wholly explained by insurance status and disease prognosticators, with greater disparities seen in OS versus EFS outcomes. Future research investigating the underlying mechanisms of disparities should consider access to, and quality of care during maintenance and among patients who experience relapse; this will likely aid in effective strategies to overcome racial and ethnic disparities.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content