All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit Know ALL.

The all Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the all Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The all and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The ALL Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Amgen, Autolus, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer and supported through an educational grant from the Hippocrate Conference Institute, an association of the Servier Group. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View ALL content recommended for you

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: an overview of etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is a malignant neoplasm clinically characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of abnormal, immature lymphoid cells resulting in clonal accumulation in the bone marrow, blood, and extramedullary sites. Despite occurring in both children and adults, it is more frequent in children, with a peak incidence in those aged 1–4 years and the lowest incidence in those aged 25–45 years. The two main types of ALL are B-cell ALL (B-ALL) and T-cell ALL (T-ALL).1-3

Etiology

The etiology of ALL is currently unknown2; however, there are various environmental risk factors and several genetic syndromes that predispose some individuals to ALL (Figure 1)1:

Genetic susceptibility2

- Congenital syndromes include Down’s syndrome, Fanconi anaemia, ataxia telangiectasia, Bloom syndrome, Nijmegen breakage syndrome;

- Inherited gene variants include, ARID5B, IKZF1, CEBPE, CDKN2A or CDKN2B, PIP4K2A, ETV6;

- constitutional Robertsonian translocation between chromosomes 15 and 21, rob(15;21)(q10;q10);

- single nucleotide polymorphisms such as rs12402181 in miR-3117 and rs62571442 in miR-3689d2; and

- rare germline mutations in PAX5, ETV6 and p53.

Environmental risk factors1-3

- Environmental risk factors include exposure to benzene, ionising radiation, or previous exposure to chemotherapy or radiotherapy

- Pesticide exposure and certain solvents or infections, such as Epstein-Barr virus and human immunodeficiencies

Figure 1. Risk factors of ALL*

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

*Adapted from Schmidt, et al.4 Created with BioRender.com

Epidemiology

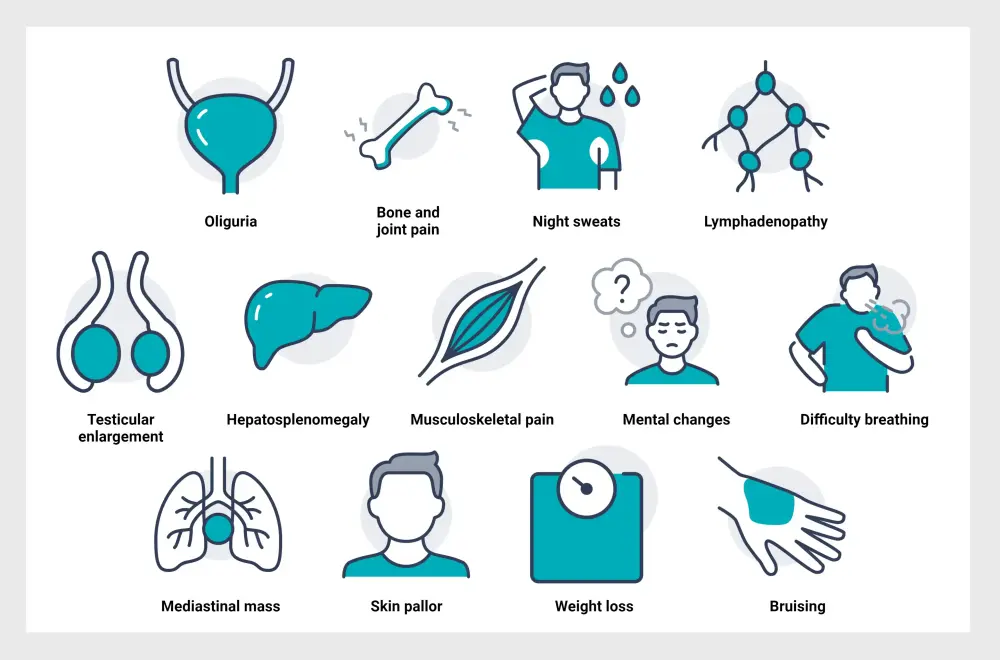

Figure 2. Epidemiology of ALL*

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Data from Malard, et al.1; Terwilliger, et al.3; Hu, et al.5 ; American Cancer Society6

Pathophysiology

B-ALL

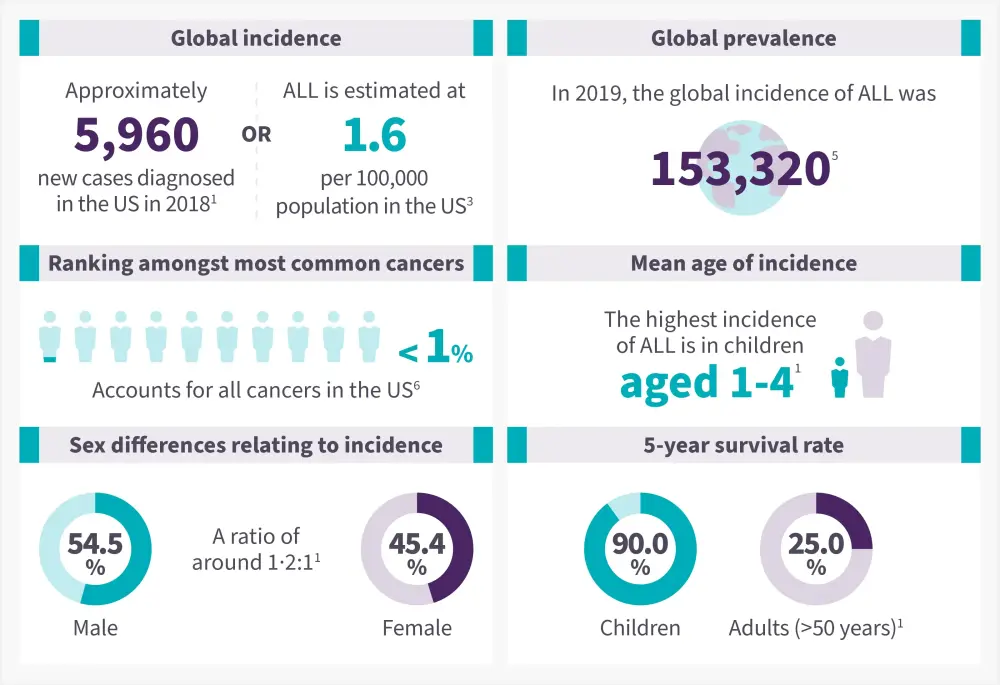

B-ALL results from a series of genetic mutations followed by clonal expansion, differentiation, cell proliferation, and dysregulated cell apoptosis. The molecular pathways involved in B-ALL pathogenesis are detailed in Figure 3.7

Figure 3. Pathogenesis and risk factors of B-ALL*

B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; IGF, insulin-like growth factor.

*Adapted from Huang, et al.7

T-ALL

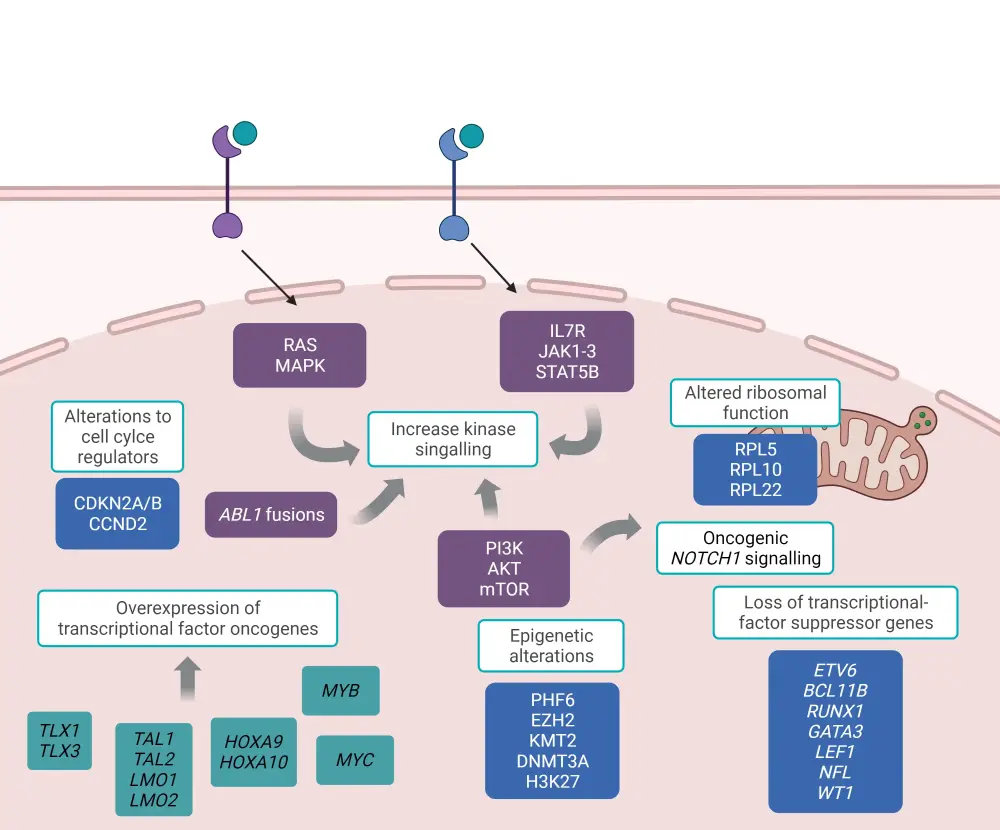

The pathogenesis of T-ALL is characterized by the accumulation of multiple genetic mutations altering cell growth, differentiation, proliferation, and survival; these include deregulation of oncogenic NOTCH1 signaling, cell cycle, increased activation of kinase signaling, transcriptional alterations of oncogenes or tumor-suppressor genes, alterations in ribosomal function and translation, and deregulation of epigenetic regulators (Figure 4).8

Figure 4. Molecular pathways involved in T-ALL pathogenesis*

T-ALL, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

*Adapted from Fattizzo, et al.8 Created with BioRender.com

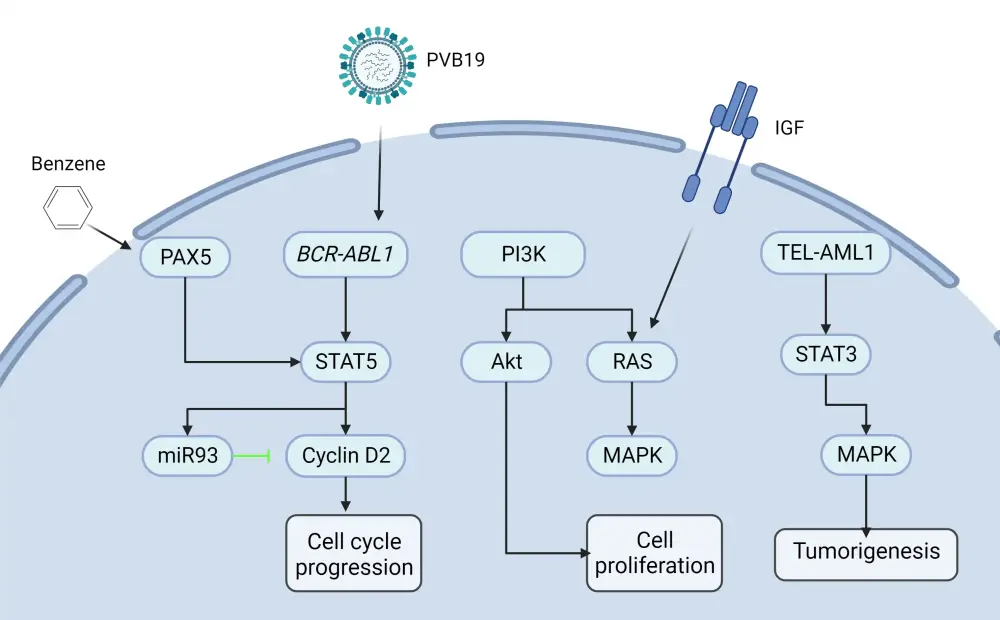

Signs and Symptoms2

The signs and symptoms of ALL are summarized below in Figure 5.

Diagnosis

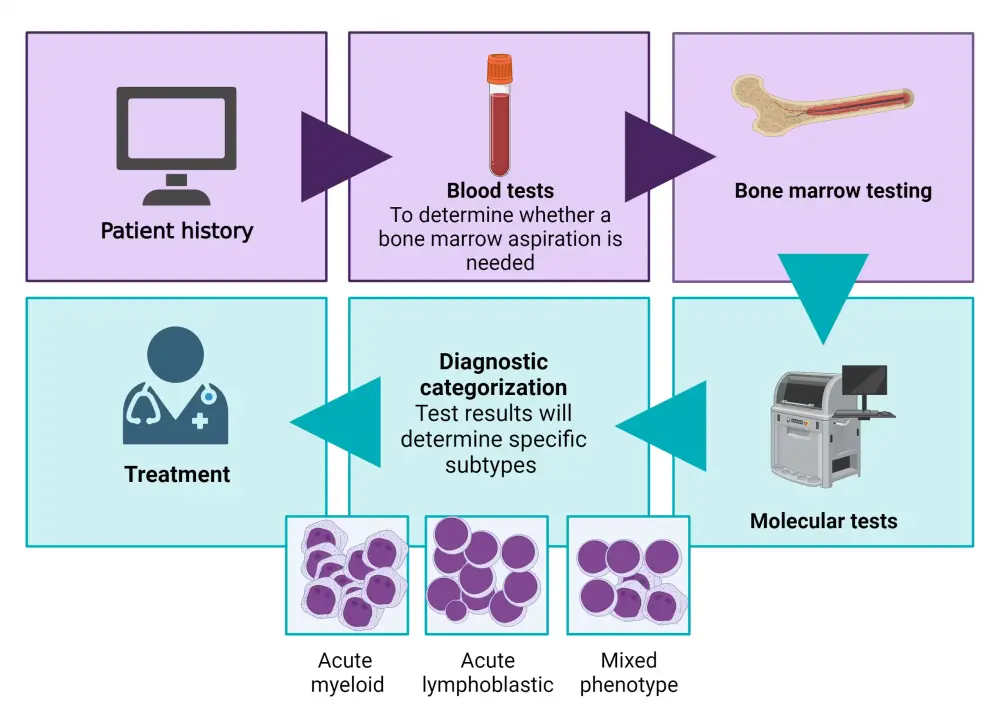

Diagnosis of ALL is defined by the presence of ≥20% lymphoblasts in the bone marrow or peripheral blood.3 Infiltration of the peripheral blood or bone marrow with lymphoblasts is identified by morphological assessment; immunophenotyping is used to distinguish B- and T-cell lineage and for risk stratification.1 According to the 2008 World Health Organization classification, the current diagnostic approach for ALL relies on a combination of morphological, immunological, and genetic/cytogenetic-based assessments.9

Key tests

Diagnostic tests for ALL include a complete blood count, a peripheral blood smear, and a bone marrow biopsy. Laboratory tests include histochemical studies, cytogenetic testing, immunophenotyping, and specific molecular and genetic tests. Lumbar punctures are performed to investigate central nervous system (CNS) involvement. Imaging assessments, such as X-ray, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound, may also be performed during diagnosis.10,11 The diagnostic journey for patients with ALL is outlined below (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Diagnostic journey*

*Adapted from Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.12

Diagnostic criteria for B-ALL

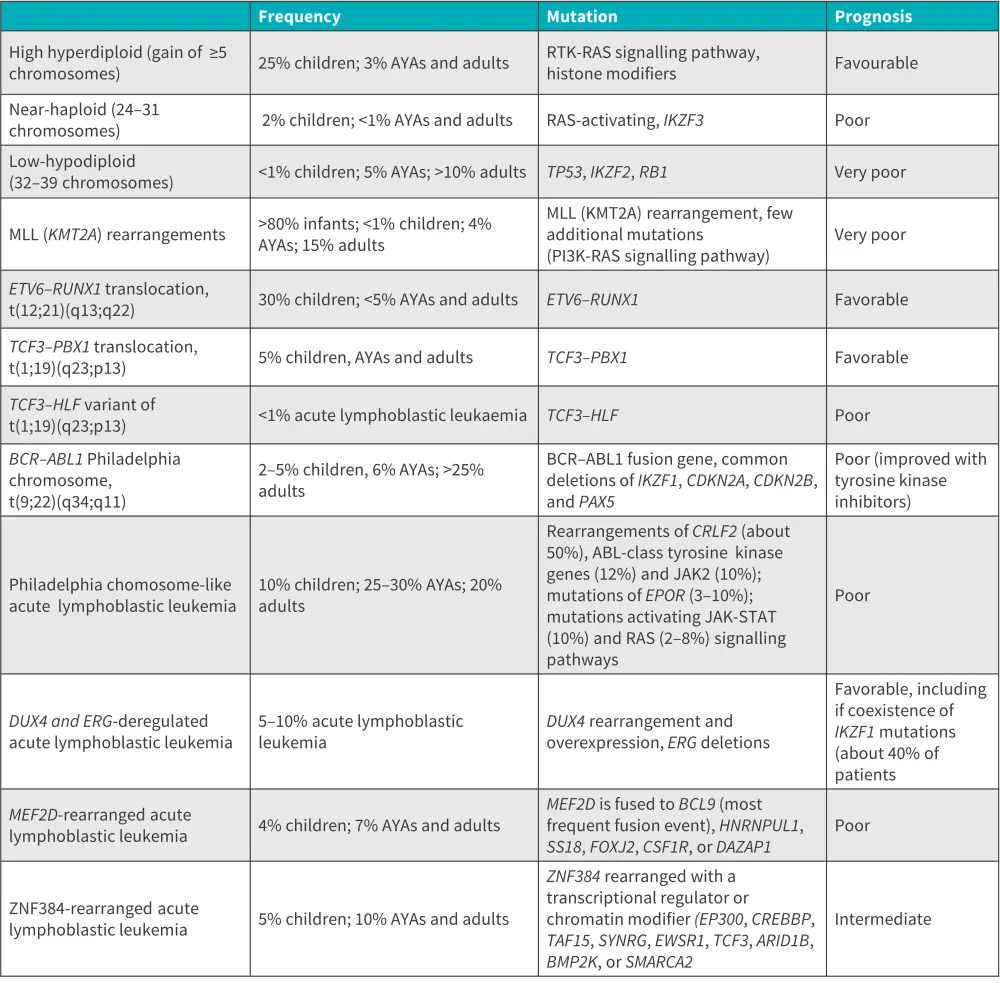

The markers for differential classification of B-ALL are CD19, CD20, CD22, CD24 and CD79a.9 The main genetic subtypes of B-ALL are described in the table below.

Figure 7. Main genetic subtypes of B-ALL*

AYA, adolescents and young adults; B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia

*Adapted from Malard, et al.1

Diagnosis criteria for T-ALL

Through immunophenotyping, CD1a, CD2, cytoplasmic and membrane/surface CD3, CD4, CD5, CD7, and CD8 have been identified as T-cell specific markers. Positive expression of cytoplasmic CD3 and CD7 is commonly seen, with variable expression of the others. In up to 25% of T-ALL cases, CD10 antigens are observed in a non-specific manner with expression of CD34, alongside myeloid markers CD33 and/or CD13.9

T-ALL subtypes associated with thymocyte differentiation stages include pro, pre, cortical, mature, and more recent early T-precursor. Each of these subtypes can be identified based on unique immunological features.9

Guidance on diagnosis may vary between countries. Below, we summarize key guidelines and further information.

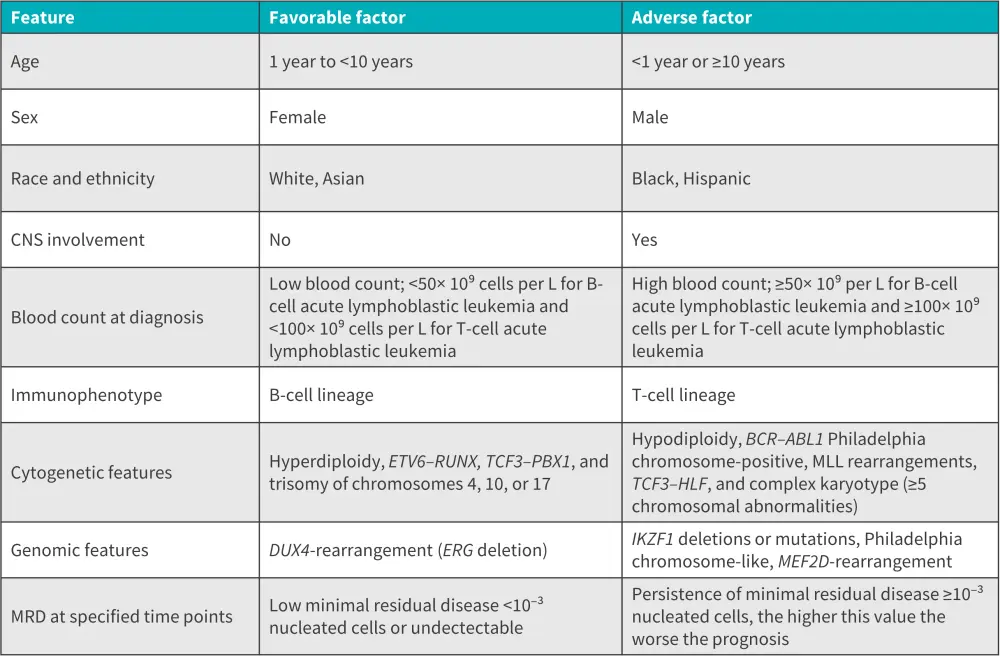

Prognostic factors

Identification of prognostic factors and accurate risk stratification is important for treatment planning.1 Some favorable and adverse risk factors for ALL are summarized below.

Figure 8. Prognostic factors for ALL*

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; MRD, minimal residual disease.

*Adapted from Malard, et al.1

Treatment

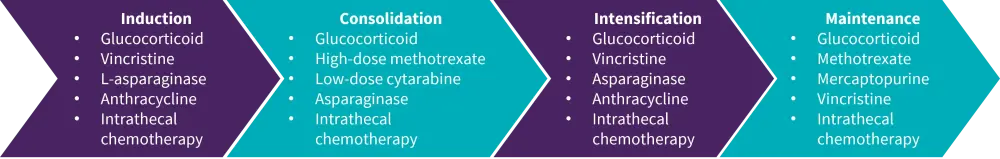

There are four phases in the first-line treatment of patients with ALL,

- initial induction, to eradicate disease burden and achieve complete remission;

- consolidation, to eradicate any remaining leukemia cells in the body that have not been identified by common blood and bone marrow tests;

- intensification, to prevent the return or re-growth of cancer cells in the body; and

- long-term maintenance, aiming to prevent disease relapse.

The phases of first-line treatment and key chemotherapy regimens are summarized in Figure 9.1

Figure 9. Phases of first-line treatment in ALL*

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

*Adapted from Malard, et al.1

Additionally, CNS-directed therapy is administered to prevent CNS relapse. Treatment strategies include intensive intrathecal chemotherapy with methotrexate alone, or methotrexate, cytarabine, and hydrocortisone in conjunction with high-dose intravenous methotrexate and cytarabine. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is a consolidation treatment primarily undertaken by high-risk patients or those with persistent minimal residual disease. Patients with Philadelphia-chromosome positive ALL are given tyrosine kinase inhibitors.1

Although disease-risk stratification and intensive chemotherapy regimens have significantly improved survival rates, there is a lack of treatments in some low- and middle-income countries, leading to disparities in survival rates.1

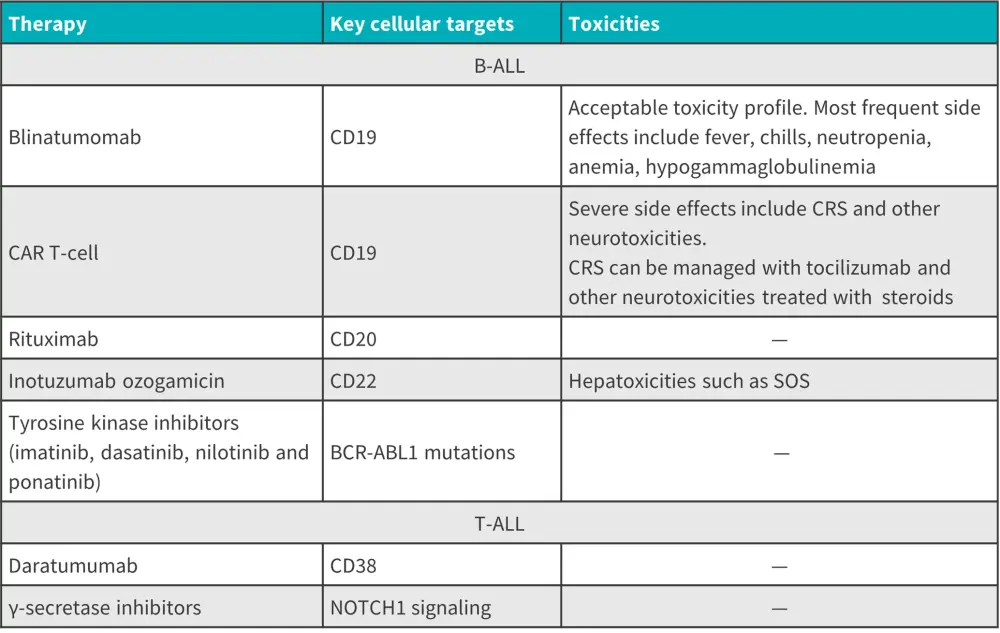

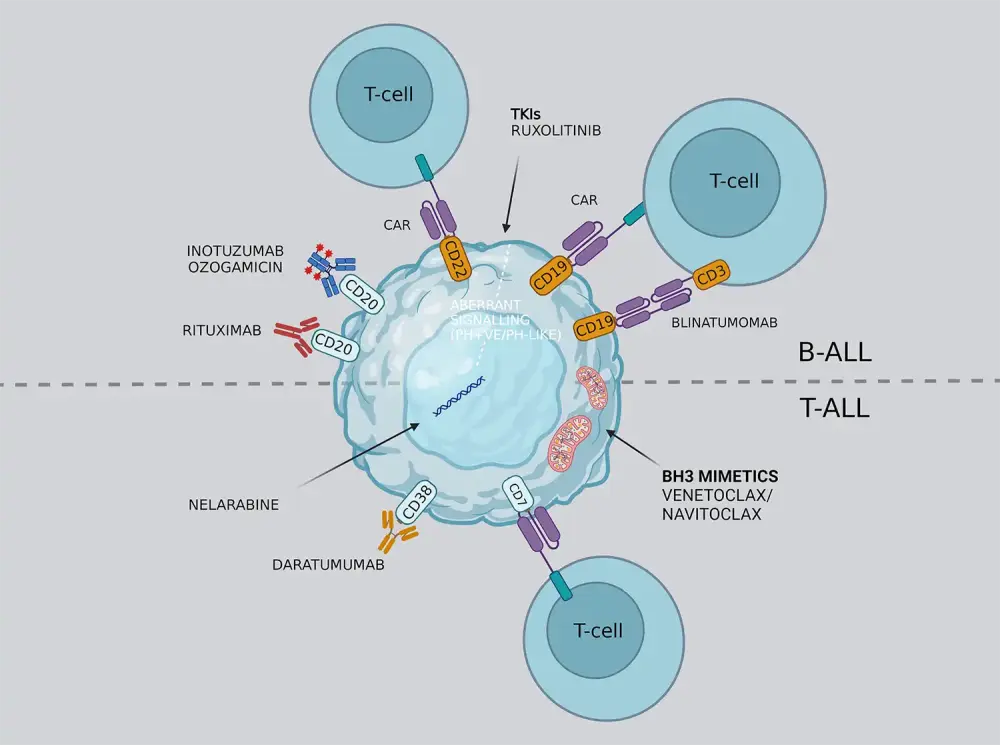

There are now several targeted therapies being utilized and developed for ALL. A summary of the targeted therapies, cellular targets, and associated toxicities is provided in Figure 10.1 A summary of targeted therapies for B-ALL and T-ALL is provided in Figure 11.

Figure 10. Targeted therapies, cellular targets, and associated toxicities*

B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; SOS, sinusoidal obstruction syndrome; T-ALL, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

*Adapted from Malard, et al.1

Figure 11. Targeted therapies in B-ALL and T-ALL*

Adapted from Salvaris R, et al.13 Created with BioRender.com

Guidance on treatment may vary between countries. Please read the section below on key guidelines for further information.

Key Guidelines and organizations

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content