All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit Know ALL.

The all Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the all Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The all and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The ALL Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Amgen, Autolus, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer and supported through an educational grant from the Hippocrate Conference Institute, an association of the Servier Group. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View ALL content recommended for you

The role of the gut microbiota in CAR T-cell therapy outcomes

Do you know... In the study by Spencer et al., which of the following was associated with longer progression-free survival and higher response rates?

Despite the high efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in hematologic malignancies, refractory/relapsed disease is common. As such, there is an urgent need to understand the factors impacting CAR T-cell therapy outcomes.1

The human gut microbiota is a system of microorganisms including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and archaea which modulate inflammatory, metabolic, immunological, and kinetic processes in the host. Over the past 2 decades, the role of the gut microbiota has been investigated in cancer, with studies showing that gut microbial dysbiosis is implicated in tumorigenesis, therapeutic effects, tumor escape, and modulation of immune responses.1

The ALL Hub previously reported on the effect of antibiotic treatment on CAR T-cell therapy response. Here, we summarize the article by Garielli et al.1 on the role of gut microbiota in CAR T-cell therapy response and toxicity and potential therapeutic approaches harnessing the microbiota to improve CAR T-cell efficacy and reduce toxicity.

Implications of gut microbiome in CAR T-cell therapy

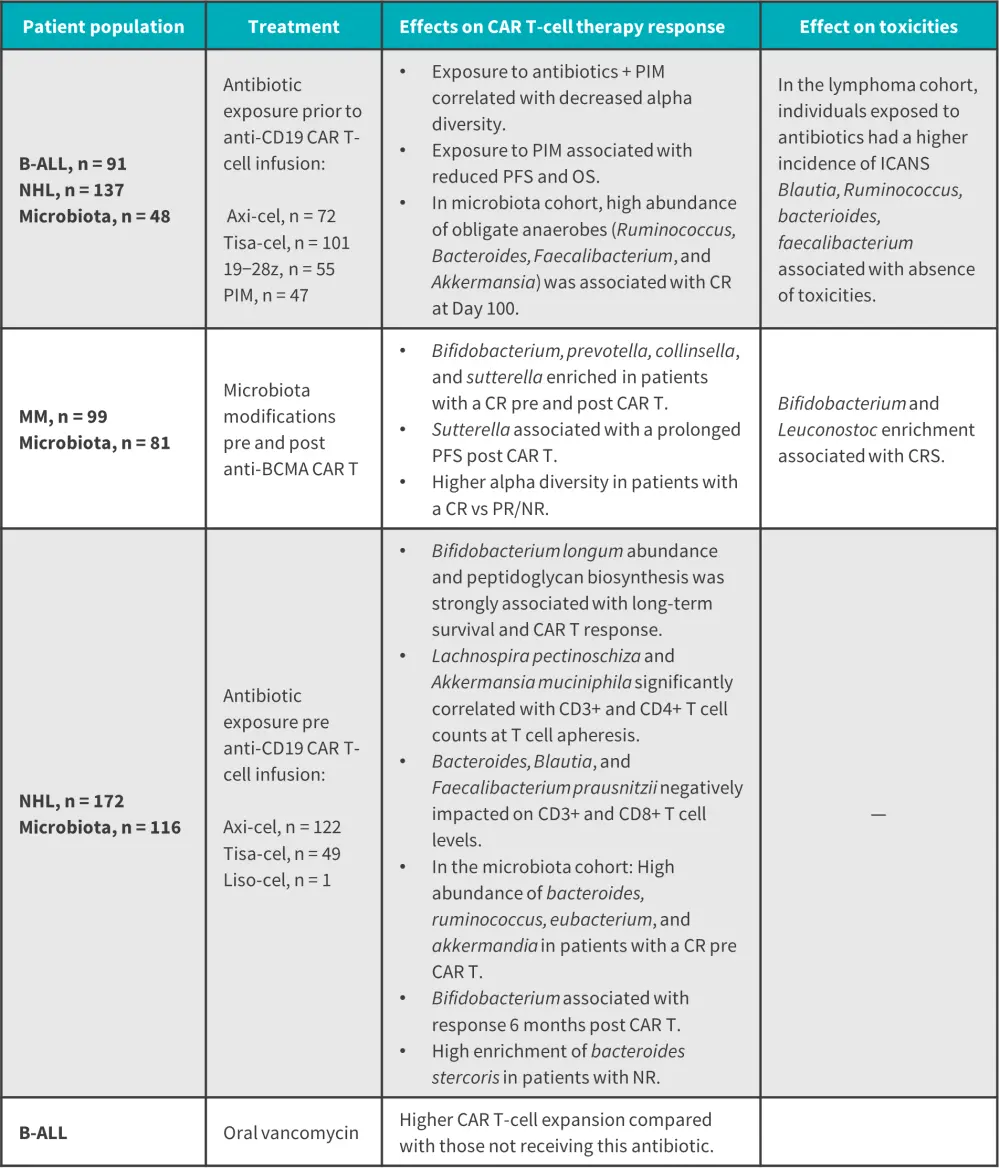

Studies have reported preliminary data on how the gut microbiota can influence the response and toxicity of CAR T-cell therapy. Table 1 summarizes preclinical data and Figure 1 reports clinical data from four retrospective studies.

|

CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CTX, cyclophosphamide. |

||

|

Treatment |

Model |

Effects on CAR T-cell activity |

|---|---|---|

|

Broad-spectrum antibiotics pre-CAR T-cell therapy lymphodepletion with CTX |

Murine model of A20 B-cell lymphoma |

|

|

Oral vancomycin after anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy |

Immunocompetent mice |

Compared with controls, vancomycin + CAR T resulted in:

|

Figure 1. Clinical data on the role of gut microbiome in CAR T-cell therapy*

B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; axi-cel, axicabtagene ciloleucel; BCMA, B-cell maturation antigen; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell; CR, complete response; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; ICANS, immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome; liso-cel, lisocabtagene maraleucel; MM, multiple myeloma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NR, no response; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PIM, piperacillin-tazobactam, imipenem-cilastatin, and/or meropenem; PR, partial response; tisa-cel, tisagenlecleucel.

*Data from Gabrielli, et al.1

Therapeutic strategies modulating gut microbiota

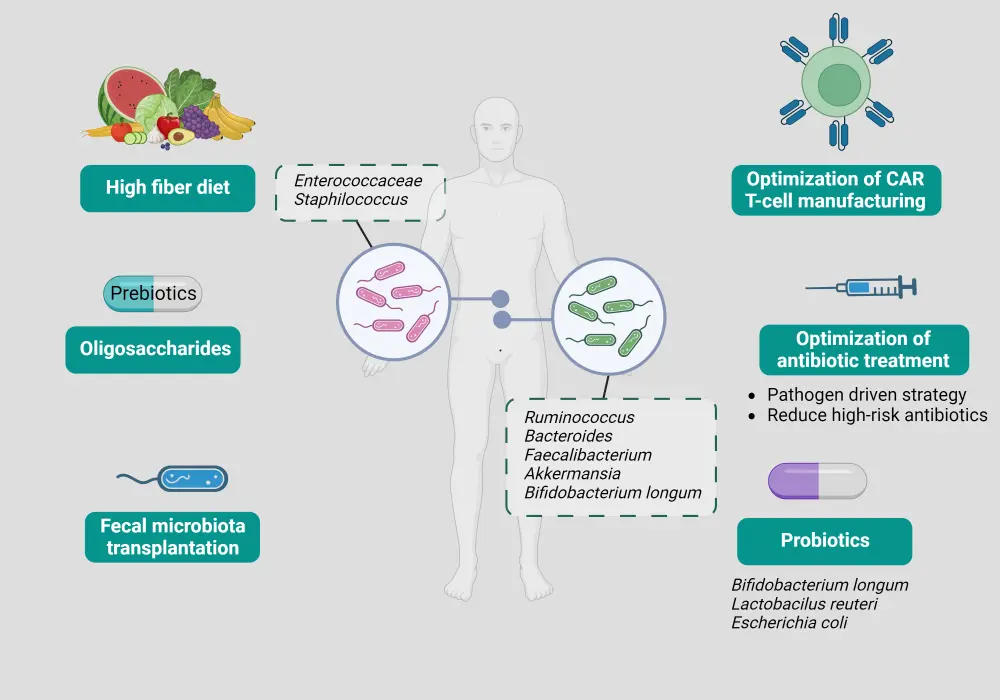

Therapeutic strategies that can modulate gut microbiota and enhance CAR T-cell efficacy include fecal microbiota transplantation, probiotics, prebiotics, dietary approaches, and adjustments in antimicrobial therapy (Figure 2). Although their role has not yet been established in CAR T-cell therapy, these interventions have shown encouraging results in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCT).

Figure 2. Therapeutic approaches modulating the gut microbiota to enhance CAR T-cell therapy*

CAR, chimeric antigen receptor.

*Adapted from Gabrielli, et al.1

Fecal microbiota transplantation

Fecal microbiota transplantation is a process that delivers a complex and diverse group of microorganisms from a healthy donor to a recipient, restoring important functions of the gut microbiome, such as providing colonization resistance, producing beneficial metabolites, and restoring crosstalk with the mucosal immune system. It has proven effective for the treatment of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections and has recently demonstrated promising results in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors and those with acute graft-versus-host disease after allo-HCT.

Probiotics and prebiotics

The use of probiotics involves direct administration of specific bacteria to modulate the gut microbiota. Despite its ability to control recurring infectious disease and metabolic disorders, its efficacy as cancer therapy in combination with immunotherapy is debated. For example, in the study by Bender et al., Lactobacillus reuteri, Bifidobacterium longum, and Escherichia coli demonstrated anti-tumor effects in mice treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Conversely, the study by Spencer et al. reported no increase in response and survival rates for patients with melanoma who were treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors and exposed to antibiotics.

Prebiotics such as inulin, fructo-oligosaccharides, and galacto-oligosaccharides are nondigestible dietary substances that stimulate the growth and metabolism of beneficial bacteria, thereby modulating the gut microbiota. Oligosaccharide mixture and resistant starch administration in patients from pre-allo-HCT to Day 28 has resulted in a lower incidence of mucosal injury and acute graft-versus-host disease.

Short-chain fatty acids and dietary approaches

In preclinical models, the short-chain fatty acid butyrate has influenced the survival and alloreactivity of T cells, hindering antigen presentation in vitro and interfering with cross-priming activity in vivo to enhance the antitumor effects of vancomycin combined with CAR T-cell immunotherapy.

The study by Spencer et al. reported longer progression-free survival and higher response rates for patients with an adequate fiber intake compared with an insufficient fiber intake, with the former having a greater abundance of microbial alpha diversity, Ruminococcaceae, and Faecalibacterium. Moreover, the study by Simpson et al reported greater immune responses and reduced toxicities after immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy for patients on a higher fiber and omega-3 diet. The use of ketone body 3-hydroxybutyrate in the ketogenic diet has been shown to stimulate production of short-chain fatty acids and Bifidobacterium which, in high abundance, can enhance antitumor activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Optimization of antibiotic treatment

Given that antibiotics can cause severe depletion of obligate anaerobes and gut microbe metabolites, compromising the efficacy of immunotherapy (Table 1 and Figure 1), optimization of antibiotic treatment could potentially enhance CAR T-cell therapy. One such strategy is pathogen-driven treatment, which could minimize gut dysbiosis and enhance immune system response, although the specificity of antibiotics may be poor. An ongoing phase II trial (NCT03078010) is comparing the effects of piperacillin-tazobactam versus cefepime, a microbiota-sparing strategy, in patients receiving allo-HCT.

Conclusion

This article highlighted the impact of the gut microbiota on CAR T-cell therapy outcomes. Several therapeutic strategies which could enhance CAR T-cell efficacy by harnessing the potential of the gut microbiota were also discussed. Further studies are needed to fully elucidate the influence of the gut microbiota on CAR T-cell efficacy, the impact of antibiotics and dysbiosis on CAR T-cell efficacy post-infusion, and to explore the clinical efficacy of treatments that utilize the gut microbiota.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content